| Penguin 14 003191 X (Photo credit: scatterkeir) |

During the many years I

worked as a reporter on daily newspapers, I only once tried to use a tape

recorder while doing an interview.

As a youth I had failed

miserably to master Pitman’s shorthand, when I took a course at a secretarial

school, but I had bought a copy of Gregg’s, a simpler method, and taught it to

myself, in a fashion. What I usually depended on to take notes was my own

half-arsed system of shorthand, combined with a private system of scribbling,

allied to an excellent memory.

I

always thought that by the time one had finished interviewing a subject, one

should already know which parts of the interview one was going to need for

one’s story, and which direct quotes would be essential.

My

only essay with the tape recorder persuaded me it was a waste of time. Far from

being able to return to the office, sit down and write one’s piece, (and have

it finished within half an hour of beginning it) one was confronted with

playing the tape back, listening to the whole interview again, and then having

to decide which parts were relevant and which merely the accompanying dross.

The

tape-recorder in these days is probably an essential item for a reporter in

view of the litigious nature of modern society but in all of my life I can

recall only once being accused of having misquoted someone: that came years

after I had retired from active journalism, in a review of a book that didn’t

much interest me, and that I had carelessly hurried through, with the result

that in the review I committed a dreadful boner which the book’s authors were

quick to pick up and point out to the editor for whom I wrote the review.

Apart

from that one shame-inducing incident, I cannot remember ever having been

accused of misquoting anyone, so my personal shorthand method seems to have

worked okay.

I was

reminded of all this in the last couple of days when, for fifty cents, I picked

up a second-hand copy of a book by Janet Malcolm, the famed

commentator-reporter for the New Yorker, which deals with the subject of

interviewers and their subjects, and the assumptions, responsibilities and

expectations that reside in both sides of this encounter.

The

book is called The Journalist and the

Murderer, was published in 1990, following its publication in the magazine,

and must have, I imagine, created considerable interest among journalists when

published. In it, Ms Malcolm investigates

a court case in which a convicted murderer, Dr. Jeffrey MacDonald, about whose

trial for murdering his wife and two children the well-known journalist Joe

McGinniss wrote a 600-page book, sued McGinniss “for fraud and breach of

contract.”

The

murders took place in 1970, but it was not until 1979 that Dr. MacDonald was

charged and went to trial. McGinniss, on the lookout for another subject that

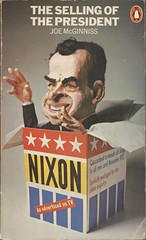

might equal the block-busting success of his first book, The Selling of the President, approached the guy, liked him, and got

himself attached to the defence team so that he could sit in even on

conversations such as lawyer-client meetings that would normally have been

denied to him as an investigating reporter.

What

attracted Malcolm’s interest was that, for the first time, a reporter was being

sued not for any mistakes of fact, but because of his attitude while

interviewing and being in correspondence with MacDonald --- an attitude of

ingratiation, friendliness and support ---- towards the subject, an attitude

that was betrayed in the final publication. MacDonald’s case was that McGinniss

had given him to believe he was sympathetic to him and his story, whereas,

having been convinced during the trial that the doctor was guilty as charged, McGinniss

described him in his book as a

psychopathic killer, a publicity-seeker, a womanizer, a latent homosexual, and

as a character who, when the layers of his mask fell away, revealed “the horror

that lurks beneath.” MacDonald had been helping McGinniss to write a book in

which he believed the author would exonerate him of his crimes, and present him

as a loving father, dedicated physician and overachiever. And this was now the

fraud with which MacDonald charged McGinniss.

All

this is of merely historical interest now, but much of what Malcolm writes

about journalism and its practice is still extremely relevant.

In

her opening paragraph she states:

“Every

journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going

on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence

man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust

and betraying them without remorse…. Journalists justify their treachery in

various ways according to their temperaments. The more pompous talk about

freedom of speech, and “the public’s right to know”; the least talented talk

about Art; the seemliest murmur about earning a living.”

I

can’t say I disagree with any of this, and Malcolm in the 163 pages of her

little book, peels off the layers of journalistic practice in a most revealing

way.

What

particularly caught my interest, however, came in an afterword she wrote, that

was tacked on to the end of her New Yorker piece. Dealing with the question of

verbatim quoting, she writes:

“…when a

journalist undertakes to quote a subject he has interviewed on tape, he owes it

to the subject, no less than to the reader, to translate his speech into prose.

Only the most uncharitable (or inept) journalist will hold a subject to his

literal utterances and fail to perform the sort of editing and rewriting that

in life, our ear automatically and instantaneously performs….”

She

then gives a literal taped translation of a reply to a question she asked a

psychiatrist who testified in the case. It occupies 19 lines of her book, and

is full of peripheral, interrupting statements in the middle of sentences, and

so on, the sort of talking that we all do, in fact, but realize how jumbled are

our statements only when confronted with them on tape. Her precis of what the

man said occupies only 10 lines of her book, but conveys exactly the message he

was trying to convey.

As

someone who practised journalism for many years, that is entirely familiar to

me, and an accurate comment on the way the profession (if I may call it that)

ought to be and usually is practised. Ms. Malcolm says that before the

invention of the tape-recorder, no quotation could be verbatim, that Boswell’s

account of what Dr. Johnson said could not have been a verbatim account of his

actual statements. All of which may be perfectly obvious to anyone who has

practised journalism.

Another

interesting addition to the debate is thrown in a few pages later, when Ms.

Malcolm goes into the meaning of the use of the pronoun “I” by journalists.

“The dominant

and most deep-dyed trait of the journalist is his timourousness. Where the

novelist fearlessly plunges into the water of self-exposure, the journalist

stands trembling on the shore in his beach robe. Not for him the strenuous

athleticism --- which is the novelist’s daily task --- of laying out his deepest griefs and shames

before the world. The journalist

confines himself to the clean,

gentlemanly work of exposing the griefs and shames of others….

But

there is a sort of exception in the work of the journalist:

“The

character (called “I” in a work of journalism) is almost pure invention, Unlike

then “I” of autobiography, who is meant to be seen as a representation of the

writer, the “I” of journalism is connected to the writer only in a tenuous way….The

journalistic “I” is an overreliable narrator, a functionary to whom crucial

tasks of narration and argument and tone have been entrusted, an ad hoc

creation, like the chorus of Greek tragedy. He is an emblematic figure, an

embodiment of the idea of the dispassionate observer of life. Nevertheless,

readers who readily accept the idea that the narrator in a work of fiction is

not the same person as the author of the

book will stubbornly resist the idea of the invented “I’ of journalism, and

even among journalism there are those who have trouble sorting themselves out

from the Supermen of their texts.”

Thanks

to the stubbornness of one of the six jurors who heard the case --- a woman who

was convinced from the beginning that MacDonald was guilty --- the verdict was

a hung jury --- the other five jurors having come to the conclusion, as Malcolm

writes, “that a man who was serving

three consecutive life sentences for the murder of his wife and two small

children, was deserving of more sympathy than the writer who had deceived

him.” Ms. Malcolm’s interest in the case

was tweaked when she received a letter from the lawyer who had defended

McGinniss, in which he said that for the first time, a disgruntled subject “has

been permitted to sue a writer on grounds that render irrelevant the truth or

falsity of what was published…Now, for the first time, a journalist’s demeanor

and point of view throughout the entire creative process have become an issue

to be resolved by jury trial.” Without

admitting any culpability, McGinniss eventually agreed to settle the case with

MacDonald, paying him some $325,000.

I

enjoyed reading the conclusions of someone who had thought so seriously about

the nature and practice of journalism, a trade I have followed all my life. Of

course, I have a tendency to interpret what she has written as meaning that, to

do the job properly, one needs not to be what I might call a true believer ---

that is, in the official myths that most or at least many journalists pursue about their craft’s essential

importance in the scheme of society. I have never been a true believer myself,

and that is not to say I have never taken the job seriously: of course, I have

always tried to do it as well as I could. But I have always avoided taking

refuge in noble shibboleths about the central importance of what I was doing.

No comments:

Post a Comment